Native American Skinwalkers

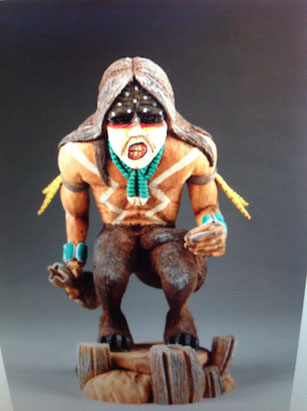

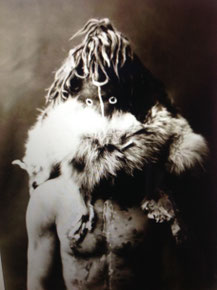

In the American Southwest, the Navajo, Hopi, Utes, and other tribes each have their own version of the Skinwalker, but each boils down to the same thing --- a malevolent witch capable of transforming itself into a wolf, coyote, bear, bird, or any other animal. When the transformation is complete, the human witch inherits the speed, strength, or cunning of the animal whose shape it has taken.

Skin walkers are purely evil in intent. I'm no expert on it, but the general view is that skinwalkers do all sorts of terrible things --- they make people sick, they commit murders.

--- Dan Benyshek, anthropologist

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

For the Navajo and other tribes of the southwest, the tales of skinwalkers are not mere legend. Rather, the belief is strongly held, particularly in the Navajo nation.

Anthropologist David Zimmerman of the Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department explains, "Skinwalkers are folks that possess knowledge of medicine, both practical (e.g., healing the sick) and spiritual (e.g., to maintain harmony), and they are both wrapped together in ways that are nearly impossible to untangle."

In the Navajo world---where witchcraft is important, where daily behavior is patterned to avoid it, prevent it, and cure

it---there are as many words for its various forms as there are words for different types of snow among the Eskimos.

We know from personal experience that it is extremely difficult to get Native Americans to discuss skinwalkers, even in the most general terms. Practitioners of adishgash---or witchcraft---are considered to be a very real presence in the Navajo world.

Few Navajo want to cross paths with naagloshii, otherwise known

as a skinwalker. The cautious Navajo will not speak openly about skinwalkers---especially with strangers---because to do so might invite the attention of an evil witch. After all, a stranger

who asks questions about skinwalkers just might be one himself, looking for his next victim.

Skinwalkers are not boogiemen and they aren't the figures made up to scare children. Unlike Anglo stories of werewolves and witches, they don't lose control and kill everything in their path or maliciously curse people for no reason.

Like humans, they do kill, and like humans, they have motivations for those acts of aggression. Power and revenge fuel their murderous intent, but such things cannot occupy the brain of a rational creature all the time, and skinwalkers do not make murder part of their daily routine.

Other than their origin story, legends of skinwalkers rarely include death or any kind of mauling. Instead, common stories include skinwalkers in their animal form running alongside a vehicle and matching their speed, even as the driver accelerates. Eventually, they get bored with this routine and simply disappear into the surrounding wilderness. In some respects, it seems rather playful, like a dog chasing a car that passes on the street.

In other instances, people report seeing or hearing skinwalkers outside their homes at night. Rarely, however, does the skinwalker enter the dwelling.

Skinwalkers have been reported by both Native and non-Native people, including a popular story here in New Mexico of skinwalkers being seen by State police on a stretch of roadway on Navajo territory.

In Navajo thinking, all good things in life result from respect for the harmony of the universe, known as hozho. An orderly balance governs the actions and thoughts of all living things.

Like any other ideal state, this can be difficult to maintain. Whether conscious or unconscious---or the result of a skinwalker---a transgression can result in illness, misfortune, or even disaster and can be remedied only with a prescribed ceremony to the offended diety. Unlike Western medicine, Navajo cures are targeted at body, mind, and spirit, calling on the patient and divine people to restore his harmony with the world.

A skinwalker is tied up with the Navajo concept of good and evil. The Navajo's believe that life is a kind of wind blowing

through you. Some people have a dark wind, and they tend to be evil. How do you tell? People who have more money than they need and aren't helping their kinfolk -- that's one symptom of

it.

Along with this tendency toward evil, if they're initiated into a witchcraft cult, they get a lot of powers. Depending on the circumstances, they can turn into a dog; they can fly; they can disappear.

A lot of Navajo's will tell me emphatically, especially when they don't know me very well, that they don't believe in all that stuff. And then when you get to be a friend, they'll start telling you about the first time they ever saw one.

--- Author, Tony Hillerman

So are they real? Who can say. In some respects, the tale of skinwalkers is like that of UFO sightings; too bizarre to picture being true, while being too numerous to dismiss.

Regardless, the tale or legend of skinwalkers is prevalent and meaningful to Native peoples in New Mexico. It is rooted in their history and tradition, and like many other things we don't always understand about different cultures, it does command our respect.

The material for this article was compiled by reviewing various sources, many online. For more information, visit the sites: www.rense.com; www.mysticpolitics.com; www.sites.lib.byu.edu