In Spanish, El Morro means The Headland or The Bluff, but the Zuni name for the ruins atop the sandstone butte is more descriptive. The Zuni's called the ruins Atsinna, which translates to Written upon the rocks. The Navajo translation for the butte is Rock upon which there is writing.

El Morro is one of the more fascinating sites in New Mexico. The large butte served as a landmark on the ancient Zuni-Acoma trail, as it provided a continuous source of water. These waters were known to historic Indians, but also to the Spanish explorers who came later. What's amazing is that the water is not the result of a spring, but rather, run-off from the snow and rains. It never goes dry, and at its most plentiful, the pool is 12 feet deep, containing upwards of 200,000 gallons of water.

For years, I have seen the turn-off for El Morro while driving between New Mexico and Arizona. Even though I've lived in New Mexico for almost 20 years, I have never thought much about the monument and never knew anyone who had ever visited. It was only more recently, while reviewing maps of the state, that I decided to venture out to this monument, situated between the Acoma and Zuni Indian Reservations.

The drive takes you from Interstate 40 south through forested areas, grassy plains, and rocky terrain. While there are hills and rock outcroppings all along the route, you see El Morro as a beacon, rising straight up to the sky.

El Morro is a cuesta, a long formation gently sloping upward, then dropping off abruptly at one end. The butte is made of sandstone layers deposited by wind, desert streams, and an ancient sea.

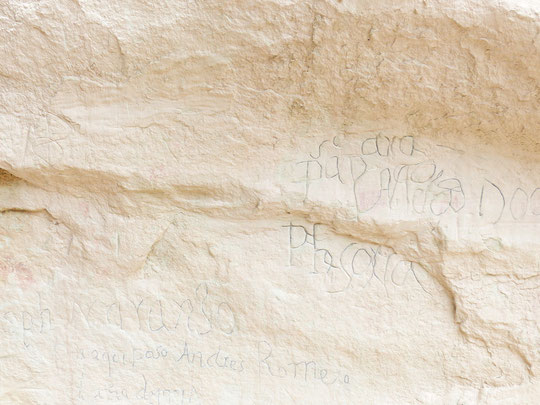

Sandstone is a relatively soft rock and the Indians were the first to inscribe their symbols---petroglyphs---and other writings into the stone.

The Indians were succeeded by early Spanish explorers, who incised into the rock their names, images, and other mementoes of their visits. The first Spanish inscription reads:

Paso por aqui el adelantado Don Juan de Onate al descubrimiento de la mar del sur a 16 de Abril de 1605

Translation: There passed by here the Governor Don Juan de Onate from the discovery of the sea of the south on

the 16th of April, 1605.

Subsequently, hundreds of other inscriptions commemorated visits by missionaries, soldiers, traders, emigrants, and tourists. It's kind of a Facebook, pre-Internet.

El Morro National Monument is 41 miles south of Grants, on highway 53. Grants is a little more than an hour west of Albuquerque. From the Visitor Center, it is a short walk to the first pool of water you will see. The trail is relatively flat, but you are at about 7,000 feet. This means you might feel a little out of breath, even after a short walk.

From the pool, you walk along the base of the butte. For approximately half a mile, you see the inscriptions at or above eye level, carved into the stone. Some are easier to see than others, as time and erosion have taken their toll on some of these. A free guidebook, available at the Visitor Center, will help you to understand the story behind some of the people who did these inscriptions.

If you just want to see the inscriptions on the butte, you can turn around at this point and head back to the Visitor Center. There, you will find a gift shop, a small museum, and a video which tells the history of the region.

If you have the time and stamina, however, I encourage you to continue along the trail, which will take you to the ruins on top of the mesa. This does require climbing, at times over boulders and sand. The trail is well-marked, but it will take another hour or so to get back to the Visitor Center going this route. There is plenty of shade from the trees, so at first, you are protected from the sun and wind. Once on top of the mesa, it's a different story, so bring a hat, sunscreen, and a coat or windbreaker.

Throughout the Monument, the Park Service has done a good job of labeling many of the native trees and plants you encounter along the way. As an example, there is a sign for the Alligator Juniper, a tree that can be seen throughout New Mexico.

Technically, its name is Juniperus Deppeana, but Alligator Juniper works just as well. It is a small- to medium-sized tree, native to central and northern Mexico (from Oaxaca northward) and the southwestern United States. It grows at altitudes of 2450 - 8900 feet in dry soil. The bark is very distinctive, cracked into small square plates resembling alligator skin.

If you like spectacular views, you are in for a treat. If you're afraid of heights, on the other hand, you may want to hang out in the Visitor Center. As you climb toward the top of the mesa, there are spectacular views to the west and north.

To the west, you see land belonging to the Zuni Pueblo. To the north, you see the southernmost territory of the Navajos. The expanse is incredible, which obviously made this a great look-out location for anyone coming for miles around.

At the point you reach the top of the mesa, you will see large fields of purple cactus. The purple color is more prominent in the winter months. The common name for this is Santa Rita [botanical name: Opuntia Gosseliniana]. It has gorgeous yellow flowers in the spring.

Also known as the Violet Prickly Pear, it is native to southern Arizona, but you will find it throughout New Mexico. You can find them for sale in many nurseries, should you want to buy some and make your own little El Morro garden.

Once you see the fields of purple cacti, your view now encompasses the full southern region, looking over the Ramah Indian area. If you look due-east, you will see some white rocks. The trail will loop north and you will be over there shortly. These two walkers, for example---visitors from Germany---were more than half-a-mile as the crow flies from where I took the photo.

Quite honestly, your biggest challenge up here isn't making the climb. If you take your time and go at your own pace, you will do fine. Rather, your eyes will constantly be pulled away from the trail in front of you to the scenery that surrounds you. Be it the expansive vistas, the unique plants, or the changing colors of the rocks, you will be amazed by all that you see up here. That alone gives you a good excuse to take a break, snap a few photos, and drink water!

The further you move away from sea level up into higher altitudes, the lower the air pressure is. Air at lower pressure has less oxygen per lungful, so your body tries to adjust by making more red blood cells to carry oxygen more efficiently. This process take several days, however, and in the meantime you might get ill.

At lower air pressure, water also evaporates faster. This can lead to dehydration. You might not feel thirsty, but you could feel light-headed or maybe feel a headache coming on. So drink lots of water on this trek. And use your sunscreen.

On the mesa, you are mostly walking among huge boulders. Because of this, the trail is less obvious than what you find in the woods. You won't get lost, though, thanks to Franklin Roosevelt's Work Projects Administration (WPA) of the 1930s.

In the 1930s, the southwest was hit with depression and drought at the same time. In a bid to ease the labor crises that had enveloped the nation and to provide long-needed public improvements, President Roosevelt signed an executive order in May 1935 establishing the WPA. Through it, the President intended to replace many of the simple relief programs, which he thought were undermining individuals' self-respect, with work projects that encouraged self-reliance and a sense of independence. New Mexico, especially, stood to gain a great deal from this project.

It was during this time that the carved-in-stone trail markers were put onto the mesa. These are still visible, intact, and efficient. But keep your eyes open and look for stacks of rocks---usually three or four small brick-size---to help alert you to the path you should follow.

Ok, call me superstitious. Or maybe I've lived in New Mexico too long, where we start to think this way. Still, I am continually amazed at the way in which sacred sites in this state have guardians, protecting over the land. Yes, there are Rangers, too. But if you look at the rocks above you---here and at many other sites in the state---you will be able to make out human or animal forms, almost as if they are watching and protecting the sacred land. You do see the face in this rock, yes? And the bird on his back?

Here is where you thank yourself for making the trek up the mesa. You are now at Atsinna.

The Pueblo people---in addition to being ingenious farmers---were master builders. Their earliest structures, half-buried pithouses, evolved into above-ground pueblos by 1000 CE. Soon, the pueblo people were building many of their villages on mesa tops, perhaps with defense in mind or simply to be high above the plain.

Atsinna Pueblo, the largest of the pueblos atop El Morro, dates from about 1275. Its builders made use of flat sedimentary rock, which was easily cut into slabs they could pile on top of one another, cementing them with clay.

The pueblo was about 200 by 300 feet, and it housed between 1,000 and 1,500 people. Multiple stories of interconnected rooms---875 have been counted---surrounded an open courtyard. Corn and other crops were grown in the irrigated fields down on the plain.

The Atsinna people are believed to be the ancestors of the Zuni. You can visit the Zuni Pueblo, but check to make sure it will be accessible to tourists when you want to go: www.ZuniTourism.com

Your climb down from the mesa is steep, but not dangerous. Just stay on the path and you will do fine. Depending on the recent rain situation, you will see pools of water tucked into the various canyons.

When you get back to the Visitor Center, do browse the museum. There are some artifacts from the region, as well as some nice story-boards which explain its history.

And remember: You didn't pay to enter the monument, you didn't pay a fee to park your car, and you didn't pay a fee to see all of this. There's a donation can in the Visitor Center; please contribute.

If you will be spending time in the region, consider visiting the El Malpais Conservation Area. Here, you will find sandstone cliffs, hiking trails, caves, fields of lava flow, and La Ventana,the largest natural arch in New Mexico. www.nps.gov/elma/

Write a comment

Katharine Jeanbaptiste (Wednesday, 01 February 2017 15:03)

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your web site offered us with useful information to work on. You have performed an impressive task and our whole community will probably be thankful to you.

Barabara Humiston (Saturday, 04 February 2017 05:19)

you are truly a excellent webmaster. The website loading velocity is incredible. It kind of feels that you are doing any distinctive trick. In addition, The contents are masterpiece. you have performed a great task in this topic!

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:06)

20

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:08)

20

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:08)

20

1 waitfor delay '0:0:15' -- (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:09)

20

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:22)

20

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:23)

20

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:23)

20

KSHWqSdC (Friday, 01 April 2022 17:26)

20